When WHO researchers decided to develop a mobile app to help identify and manage skin-related neglected tropical diseases – or skin NTDs – and common skin conditions, they hoped it would support frontline health workers (FHW) in resource-limited regions where dermatologists are in short supply. What emerged from the field, however, was something more: health workers widely reported that the app helped build their knowledge and clinical confidence – that meant they could often manage skin conditions locally, without needing to refer patients to higher-level facilities.

“Frontline health workers told us the app motivated them to independently research and learn about these skin diseases themselves, making them feel empowered,” said Emily Quilter, a researcher at the University of Bristol’s Centre for Doctoral Training in Digital Health and Care who is involved in an ongoing study in Kenya to assess the app’s impact.

“They reported that they were telling their colleagues, ‘If you see a skin condition, you send the patient to me.’ That’s a huge shift in how they see their role.”

Skin diseases affect 1.8 billion people at any point, and in most tropical and resource-poor communities about 10% of those are skin NTDs, according to WHO estimates. The most common, including leprosy (Hansen disease), Buruli ulcer, cutaneous leishmaniasis, yaws and scabies, often lead to chronic disability and social stigma if not diagnosed and treated promptly. But in many countries, there are too few specialists who can help – most of the African continent has fewer than one dermatologist per million people, compared to 36 per million in the US.

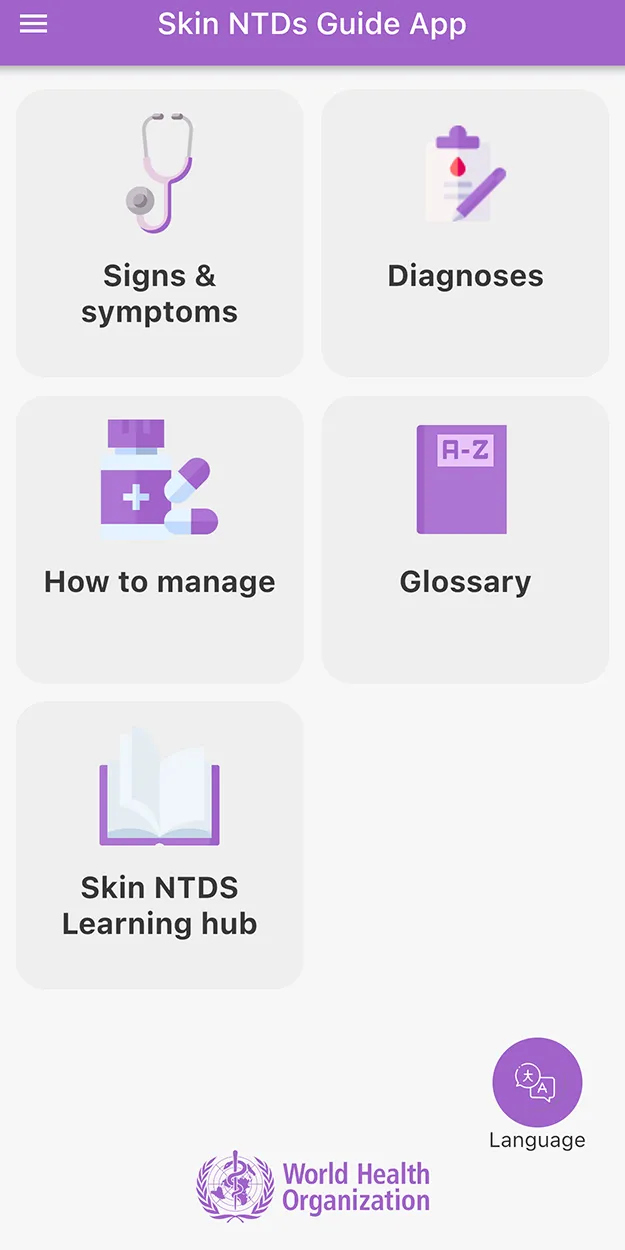

WHO designed the Skin NTDs App to put dermatological knowledge in the hands of nonspecialist frontline health workers. The free, multilingual tool helps them diagnose and manage the most common endemic skin conditions. The standard version of the app works offline, enabling healthcare workers in remote areas to use it even without internet access. With a new AI-driven version, still in the beta testing phase, health workers can compare images of their patients’ skin lesions with thousands in an online photo library.

The app is part of a wide-ranging effort by WHO and its partners to support the eradication, elimination or control of skin NTDs, including publication of the skin NTDs framework, a guide for countries on how to implement integrated management strategies for skin NTDs. The global health community will be turning the spotlight on skin NTDs this week, when the 78th World Health Assembly is expected to adopt a groundbreaking resolution to recognize skin diseases as a global health priority.

We spoke with the team working on WHO’s Skin NTDs App about the app’s success so far, how it is democratizing skin healthcare and plans to boost its impact with artificial intelligence.

How does the Skin NTDs App work?

Dr José Antonio Ruiz-Postigo, medical officer in the WHO Global Neglected Tropical Diseases Program: The app has two main components. The first one, which is publicly available and works offline, was developed in collaboration with Universal Doctor and the nongovernmental organization Until No Leprosy Remains. It has information on how to manage skin conditions, which ones to suspect based on certain signs and symptoms and maps showing in which countries each skin NTD is endemic. It also provides the user with a decision tree tailored to any countries the patient has been to. So if they were in, say, South Sudan, the list of possible skin NTDs will only contain those that are endemic to that country. Otherwise, it would be overwhelming and useless.

The second component is powered by AI – it’s still being tested in the field and isn’t publicly available yet. For now, it requires internet access. Developed by Universal Doctor and Belle.ai, it uses AI-based algorithms to instantly classify and identify 12 skin NTDs and 24 common skin conditions. When you upload a photo of a skin condition to this version of the app, it compares the photo to a database of thousands of photos and offers up a shortlist of diseases that the patient could be suffering from. Based on this information, the health worker can carry out a standard interview and physical examination to eventually decide which disease is affecting the patient.

We are in discussion with the app developers about creating a way to allow frontline health workers access to the AI-driven version without relying on internet access. We have done some trials, so we know it works. We just need the funding to develop it out. If we can do that, we can make the full power of the app available to anyone, anywhere. It really will be a game changer.

You carried out the first comprehensive assessment of the app’s impact in Kenya in 2024. What did you learn?

Ruiz-Postigo: We saw that it got a sensitivity rate of around 80%, meaning most users found the app accurately suggested which skin disease a patient was experiencing. A regular family doctor without training in dermatology will make the right diagnosis in about 20-40% of cases, and that is the same whether you are in Kenya or the UK. So, 80% is excellent.

Carme Carrion, principal investigator at the Open University of Catalonia eHealth Center: It’s important to note that the main goal of the app is capacity building, it’s not meant as a diagnostic tool. It’s designed to improve the knowledge and skills of people who have not been trained enough about the most common endemic skin diseases in their area.

And it appears to be working. During our interviews with healthcare workers using the app, we spoke with one doctor with many years of experience in a rural area in Kenya. He told us about the time he uploaded a photo to the app, and it told him it could be leprosy. He was convinced the app was wrong, because leprosy hadn’t been seen in that area for hundreds of years. When he got the same result with another patient, he decided to look back at his old research books and realized that, yes, it was leprosy.

That is the outcome we’re aiming for. The app made someone realize where they had a gap in their knowledge, motivated them to gain that knowledge and led them to the right treatment.

Was there anything that surprised you about how the app is changing the way health workers do their jobs?

Quilter: One of the most profound findings for us is frontline health workers reporting a shift in dermatological case management. Previously in Kenya, they described a culture of habitual referral. They said they would encounter patients with skin conditions and without examination almost unanimously refer them to a specialist dermatologist. But there were so many patients lost to follow up because there are very few dermatologists in Kenya, and many people can’t afford it or can’t travel the hours it takes to see a specialist.

Health workers told us the app made them more confident to manage patients with common skin conditions at the local facility level. Then in cases where their clinical judgement didn’t align with the app’s diagnostic suggestions, they would refer the patient to a specialist dermatologist. Those conversations show us that the app is being used as a partner instead of a diagnostic authority, which is encouraging.

They also told us the app contributes to the destigmatization of skin NTDs. That’s really important given how stigma impacts access to healthcare. Before the app, uncertainty around diagnosing skin conditions meant that patients who went into a facility for a consultation would basically be surrounded by doctors having a public deliberation over what it could be. In a way, it made the patient a spectacle, which health workers told us often contributed to the patient feeling stigmatized. They said that having the app available to them removed the need to bring colleagues in to corroborate a diagnosis and helped restore the patient’s privacy.

What’s next for the Skin NTDs App?

Ruiz-Postigo: We’re writing up the assessment from the Kenya trial, but we know we can’t make a global recommendation for the whole world based on one trial. So, we are now looking at carrying out assessments in Cameroon and Côte d’Ivoire next. And we are in discussions with teams in Brazil, India and Indonesia, so we can see the results in other contexts with different skin tones and different conditions in different societies.

Quilter: We’re also carrying out a series of ethnographic studies in five counties in Kenya, implemented by the University of Bristol and Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) with financial support from the University of Bristol and WHO. These studies will use participant observation and interviews to examine how the app is used in practice by FHWs. Our aim is to understand the complex social, cultural, infrastructural and economic factors that shape how people use the app – including how patients experience this kind of AI-powered tool in real-world care.